I should perhaps say a word or two about vanity publishing. Many writers have published their own work, among them some of the most eminent in the core tradition of American literature. Many more have taken part in cooperative publishing. For a writer to seek out a printer and arrange to have his work brought out is testimony of his faith in himself; he may — probably will — lose money, but at least he will not be paying some vanity publisher to lose it for him, and double the sum he will lose … Self-publication need carry no stigma; but vanity publishing certainly does.

(Derleth, “My Life in Poetry”)

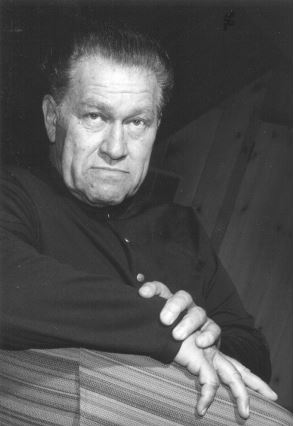

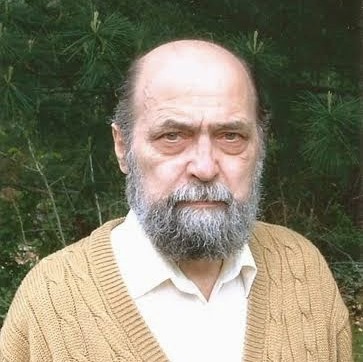

Wisconsin writer and publisher August William Derleth (1909–71) skirted the label of vanity publishing, despite issuing hundreds of books under four owned imprints, including numerous titles of his own. Doing so successfully required not only adroit maneuvering, but frequent explaining.

Of the four publishing ventures, is there any connoisseur today who has not learned of Arkham House, Derleth’s pioneering specialty press established in 1939 to publish exclusively supernatural fiction? Its books still fervently sought and collected today — still trading at ever-climbing prices?

Arkham’s first was the omnibus The Outsider and Others, a huge collection of tales by H. P. Lovecraft, first as well by that now-famous author. But Arkham’s second was Someone in the Dark, a Derleth title, the first to raise the specter of vanity publishing and the need for the following oft-repeated explanation:

What changed my mind about publishing more widely was the collecting of my own first book of ghost stories. My contract with Scribner’s, who had by this time published several of my historical novels and other books, called for first rejection rights on any manuscript prepared for publication. I accordingly sent them the manuscript of Someone in the Dark. In rejecting it — again on the basis of potentially too slender sales — Bill Weber suggested that, since I had an imprint specifically related to the field in Arkham House, I ought to publish the book myself. I replied that I did not look with favor on anything that smacked of vanity publishing. He in turn answered that the difference between vanity publishing and good business was the difference between throwing away money to gratify vanity and making it on a sound publishing venture. He explained that, if Scribner’s published Someone in the Dark, they could sell at best 2,000 copies at a retail price of $2.00, and thus earn for me something like $400.00 in royalties. At the most generous estimate, reprint sales might bring in another $500.00, which, by contract, must be shared with the publisher. If, however, I published the book myself, no such division of income would be necessary.

(Derleth, “All ‘Round Bookman”)

In 1945 Derleth launched a “companion” imprint, Mycroft & Moran, to gratify fans of a small subgenre of fantasy: occult detective stories and Sherlock Holmes pastiche. Because he revered the famous Great Detective of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, M&M became a vehicle for the adventures of Solar Pons, Derleth’s pastiche of Sherlock Holmes — most of which had been previously published, separately, in scattered periodicals.

As a rule, for all authors, the two imprints were used to collect or anthologize stories already published. But there were occasions when Derleth composed a new short to “round out” a collection. And he did add stories to his own to The Survivor and Others that were sitting in the queue, publication pending, when Weird Tales magazine — pretty much the only surviving market for these tales — suddenly stopped publishing.

These liberties only affected this commercial vein of Derleth’s writing, the fiction he referred to collectively as “entertainments,” a small — in the author’s mind inconsequential — portion of his total output.

Also in 1945, for serious work — the novels, novelettes, short stories and poems he wrote about rural Wisconsin — Derleth christened his third imprint, Stanton & Lee. Most titles of this list were reprints of books published by other publishers. Necessary, Derleth believed, because all pieces of his “saga” were connected, and it was a way to keep the necessary titles in print and whatever else he fancied to publish, even collections of popular cartoon strips. Ostensibly, even with Stanton & Lee, Derleth managed to sidestep the vanity publishing charge.

Decades later Derleth introduced a nonfiction book to mark a landmark anniversary — Thirty Years of Arkham House: 1939-1969 — a “comprehensive bibliography of the publications of Arkham House and its subsidiary imprints throughout the [first] 30 years of its existence.” Purportedly, he was describing all of the books he had published. But in fact he omitted a fourth imprint for reasons never explained. But, in “Hawk & Whippoorwill: Derleth’s Overlooked Imprint,” I discerned a partial explanation, but more importantly how H&W served as a Stanton & Lee “name-change” during the period when Derleth was issuing poetry books.

And how Derleth’s precise wording in the bibliography itself revealed a likely motive — “Arkham House and its subsidiary imprints” — the use of “its” being the operative word, not Derleth and his owned imprints — by suggesting a cost in time and money that for him was prohibitive. How recording the contents of the missing books, adding pages of H&W journal and collection poem titles would for a relatively low-demand book, of limited interest to a subset of Arkham House patrons, nudge expenses up to an unacceptable level.

Besides, there was more that should have been mentioned…

Because the threads that bound Derleth’s self-publishing efforts involved yet a fifth imprint: The Candlelight Press of New York and Copenhagen. Ownership notwithstanding, Candlelight may be the gray area regarding Derleth and vanity publishing.

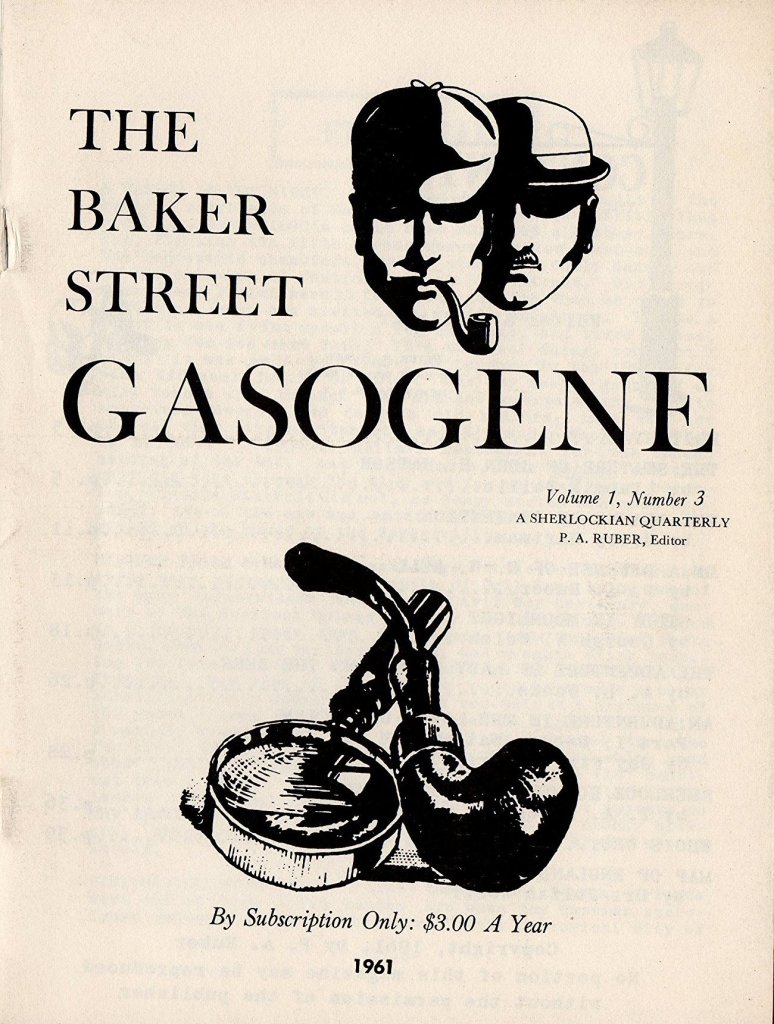

Candlelight Press did not exist when Peter Ruber lived in New York, 1960–62, employed as the Advertising and Public Relations Director for a major food service organization. In his spare time, he had edited The Baker Street Gasogene, a Sherlockian journal to which Derleth happened to subscribe — all that Peter Ruber knew of Derleth was a handful of Solar Pons stories he had stumbled upon in magazines.

Learning that the Gasogene was failing, Derleth, an advocate of this sort of “Little Review” publishing, offered gratis a short piece on Solar Pons, which Ruber accepted gratefully and published in the fourth issue. Although the “Sherlockian Quarterly” did fail, there began between them “a friendly correspondence for a decade, exchanging letters about mutual literary interests and business.”

Ruber had also been working on an informal “biography” of a mutual friend, journalist, bibliophile, and author, Vincent Starrett, whom he occasionally visited in Chicago.

Serendipity!

As did Derleth, Ruber not only cherished The Great Detective, Sherlock Holmes, but also The Great Bookman, Vincent Starrett. And before long, he would also cherish That Other Great Detective, Solar Pons, and That Other Great Bookman, August Derleth! “August was as much a literary anachronism as the old bookman I was writing about….”

Derleth invited Ruber to visit nearby Sauk City, which he did May 1962. The two discussed publishing, Ruber writing later, “I have taken your advice about calling the VS work The Last Bookman — I personally think it is a grand suggestion.”

Together they planned to publish Derleth’s memoir of three acclaimed regional authors: Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, and Edgar Lee Masters. The latter especially had impacted Derleth’s early regional work — notably the ongoing series of poems that appeared for years under the banner “Sac Prairie People,” modeled upon Masters’ singular Spoon River Anthology epitaphs about life in neighboring Illinois. Originally merely a pastiche (as Derleth did of other favorites, including Doyle, Thoreau, and Lovecraft), “Sac Prairie People” evolved into an ongoing homage.

Most importantly, Ruber and Derleth decided to launch a new publishing imprint that would hail from “New York and Copenhagen” (the latter location, presumably, relating to Ruber’s forbears). One that would provide the degrees of separation Derleth needed, a bulwark to show, as he so often groused, “it wasn’t vanity publishing if the books sold”:

Now, there is nothing wrong in a publisher’s sharing costs with an author. It is sometimes done by reputable publishers with highly specialized books, and it is honestly done. The author should know, however, that reviewers all know the vanity press imprints; that books bearing these imprints are very seldom reviewed; and that a certain stigma attaches to an author who is unwise enough to seek publication through a vanity publishing house. At the same time it is perfectly true that many good books never find publishers, especially in this period of relatively high production costs, and the temptation to produce one’s own book is naturally perfectly understandable and wholly honest.

(Derleth, “The Author and His Public”)

In late 1963, The Candlelight Press debuted with two paperbound titles: Derleth’s Three Literary Men and Ruber’s The Last Bookman. (Also published: two small chapbooks in the mystery-detective field: Finch’s Final Fling, by J. A. Finch, and Strange Studies from Life, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.)

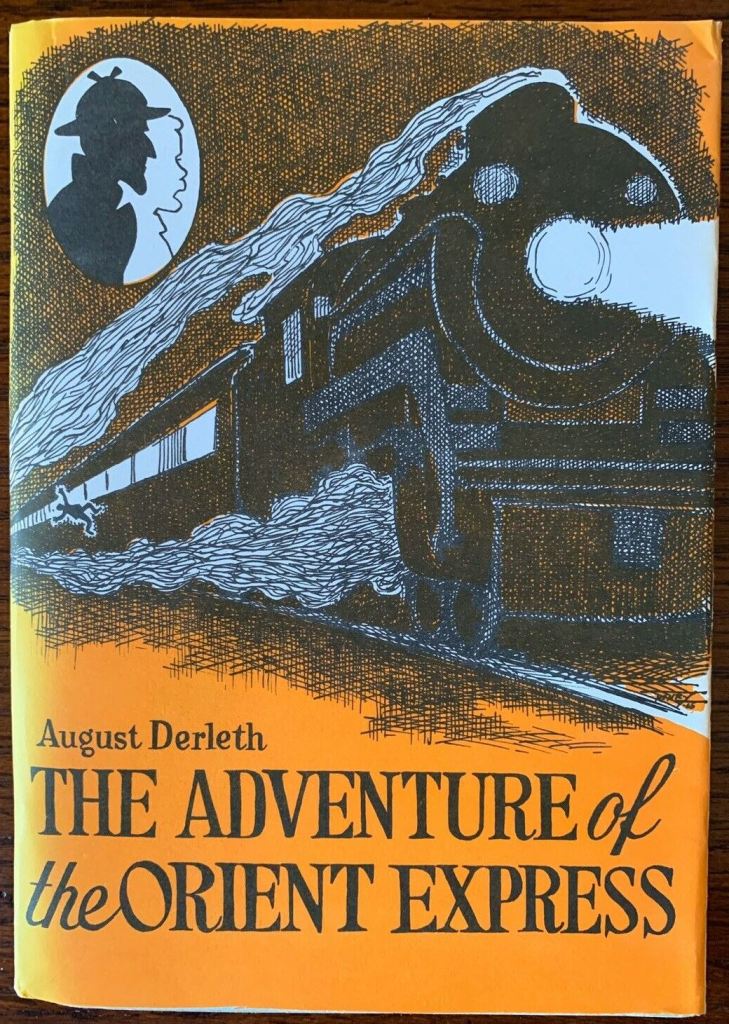

Another two were on the drawing board: Praed Street Studies (published as Praed Street Papers) and the off-trail “The Adventure of the Orient Express,” which Derleth described:

It is tongue-in-cheek … all the way through while being done straight; only aficionados of the detective story may catch it … it just isn’t the sort of story that will go over with a magazine.

Derleth to Ruber: April 9, 1963

Duly published, the two chapbooks appeared in 1965. As the introduction to Praed Street Papers, Ruber’s “A Weekend with August Derleth” dramatized the 1962 Sauk City visit. Overall, it is generally accurate, fulsome, even creative, but Derleth, after receiving his copy, in a letter dated June 17, 1965, called out two dozen little details Ruber ad-libbed:

I have no very great feeling of pain about all this, I hasten to assure you, though it comes close to making me out a sort of boor; it is only that as this sort of imaginary accounting builds up, it becomes ever more and more difficult to separate fact from fiction, and in time the legend simply outgrows the facts.

Although he understood that the slightly-larger-than-life-character Ruber shaped was only to further interest in himself, Derleth filed for posterity a carbon copy of the corrections letter — a patented tactic he did often to head-off controversies.

The relationship between Ruber and Derleth continued to flourish. In “A Portrait of August Derleth,” Ruber reveals how before visiting Derleth he had stayed awake nights “devouring his life’s literary output.” And how it pleased Derleth to learn he favored the “Sac Prairie stories better than his detective or macabre fiction….”

Having a publisher based in New York was important to Derleth — a presence in that literary mecca, on the fringe at least. Years earlier, in the mid-1940s, Derleth reached enviable heights with his books published by the prestigious firm of Charles Scribner’s Sons, and even as the Ruber years began, he was affiliated with another Big Apple publisher, Duell, Sloan & Pearce, but he was also weighing what that arrangement afforded him against other avenues more lucrative. Sales figures of Arkham House books were burgeoning, with commitments in place for many more — resources were limited, especially time. (Only one Mycroft & Moran book and one Stanton & Lee book had been published 1963–65, the latter a Scribner’s reprint — the same interval during which Derleth brought down the curtain on Hawk & Whippoorwill, ending the journal he edited and discontinuing the imprint altogether.)

Thus with Ruber, as he suggests himself in “A Portrait of August Derleth,” Derleth saw another way forward:

Due to his instigation I put myself into hock over my ears and formed a publishing company specializing in regional and literary books, and August was the center of it, helping me to distribute certain titles through his own publishing venture, Arkham House….

The pot now boiling, Derleth visited New York City in 1965. Between face-to-face meetings, he teased Ruber with routine updates, reporting on January 3, 1966 how he had completed a “a segment of Return to Walden West” and “must soon begin my next junior novel.” Augmenting frequent letter exchanges, Ruber cited the “innumerable telephone conversations.”

At some point, seemingly, this decision: The Candlelight Press would fulfill the purpose ceded by moribund Stanton & Lee. Years later in the introduction to Country Matters, Ruber shed light on how the entire arrangement also benefitted him:

I became his primary publisher in 1965, after Duell, Sloane & Pearce’s parent company, Meredith Press, decided to shift its editorial focus to more commercial literary properties. Having a New York publishing imprint for the Sac Prairie Saga was important to August; and having an established writer with his credentials on my list was a distinct advantage to me. It was the ideal foundation for a business arrangement. The association gave him control over what he wanted to have published, instead of being subjected to the usual editorial board scrutiny at Duell. In addition to my retail and library distribution, August distributed his books to his Arkham House patrons, and benefitted from the maximum distributor discount on top of his royalties, thus maximizing his income.

Plus, he shares an insight into the unique relationship Derleth required of publishers:

But getting his books into print was often a stormy affair. August wasn’t the easiest man to work with. He was bull-headed, opinionated ─ sometimes he was just damned pushy. Not all of his publishers understood his compulsive need to be in control. I would often infuriate him by not jumping at his advice. He was involved with all aspects of production, from cover designs to page layouts, and we frequently locked horns over these issues.

Essentially the propensities that led to the break with Scribner’s, which caused Derleth to begin his own Stanton & Lee label. This time he was moving more cautiously, but on May 11, 1966 he wrote Ruber:

I haven’t broken with Duell. They are still publishing for me, but primarily the junior novels; they have nothing major of mine coming and are not likely to have, though they continue to want to see the serious adult work I do; I don’t feel committed to them, though.

Nothing more need be said.

The New York Times hailed The Candlelight Press “interesting,” and the Chicago Tribune labeled Candlelight the “exciting … new-comer in publishing”; from 1963 on, for the remainder of Derleth’s life, new Candlelight titles (nearly all of them by Derleth) emerge to fit seamlessly the S&L / H&W legacy:

Hawk & Whippoorwill 1960-1963 (H&W 1963)

Three Literary Men (CL 1963)

Brief Argument (H&W 1964)

Restless is the River (S&L 1965)

The Adventure of the Orient Express (CL 1965)

Praed Street Papers (CL 1965)

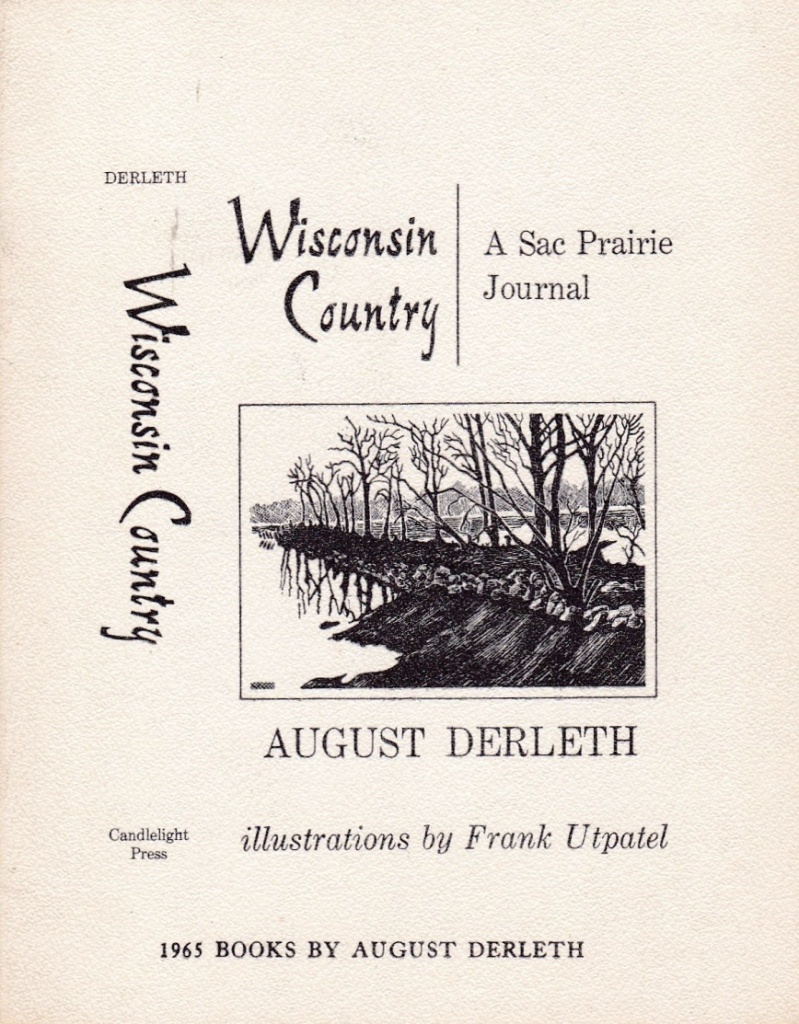

Wisconsin Country (CL 1965)

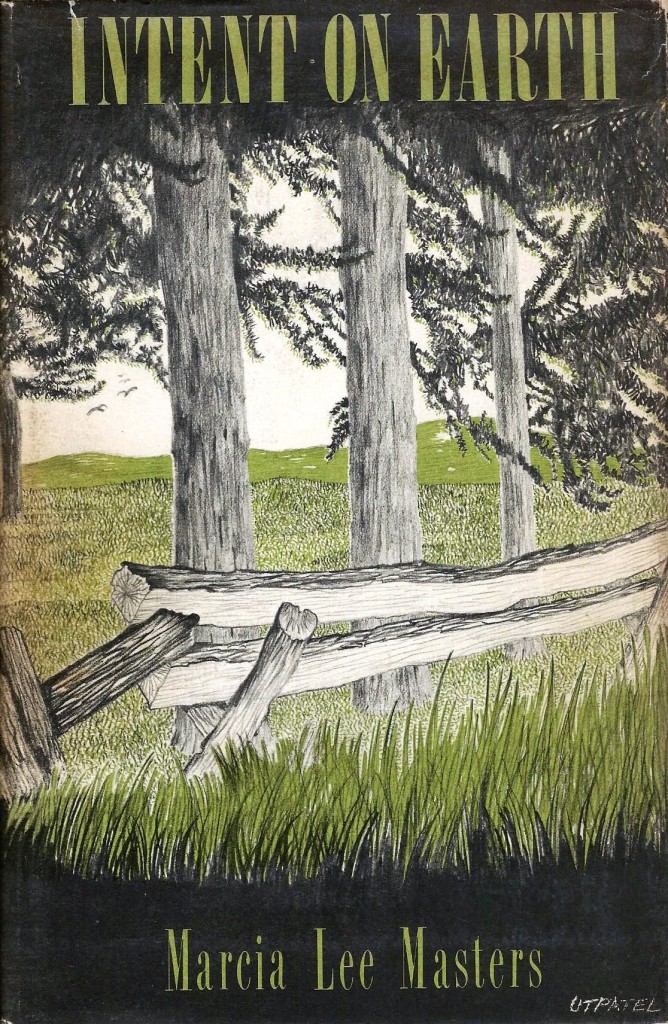

Intent on Earth (CL 1965)

A Wisconsin Harvest (S&L 1966)

The House on the Mound (S&L 1966)

Eyes of the Mole (S&L 1967)

Collected Poems (CL 1967)

New Poetry Out of Wisconsin (S&L 1969)

A House Above Cuzco (CL 1969)

The Wind Leans West (CL 1969)

Three Straw Men (CL 1970)

Return to Walden West (CL 1970)

Corn Village: A Selection (S&L 1970)

This Undying Quest (S&L 1971)

Night Letters, S&L 1971: first edition Frances May poems [Villiers]

Love Letters to Caitlin (CL 1971)

Indeed, one book on this list proves Derleth’s behind-the-scenes Candlelight involvement — Intent on Earth by Marcia Lee Masters, which has (typical of the other four imprints) a jacket by the Wisconsin artist Frank Utpatel, and this colophon:

Five hundred copies of this book have been printed

from Linotype Caledonia, by the Collegiate Press, The

George Banta Company, Inc., Menasha, Wisconsin. The

paper is Old Style Wove, and the cloth is Bancroft Devon.

Although a poet of merit herself, how does one overlook Marcia’s father being the celebrated Spoon River poet and how, because of that fact, she met — and for a period of time had been engaged to marry — August Derleth?

In Derleth: Hawk…and Dove, Dorothy Litersky not only notes Marcia’s collection of poetry, long underway, but a relationship renewed: “In late 1962 … their romance … sparked back to life briefly.” She adds:

Marcia and August kept in touch, meeting for lunch when Derleth was in Chicago … and when Derleth initiated the establishment of a vanity publishing house to provide a New York outlet for his reprints, Marcia’s poetry volume, Intent on Earth [was] published….

The reference above — Derleth’s vanity publishing house — was not a slip. Nor was the following comment made by Derleth’s close friend Donald Wandrei, in a August 25, 1975 letter to the Wisconsin State Historical Society: “All of the Derleth imprints were privately owned: Stanton & Lee, Arkham House, Mycroft & Moran, Arkham House Publishers, Candlelight Press, etc.”

The Candlelight Press!

These days, because of everything above, The Candlelight Press should interest not only S&L / H&W completests for the books, but also Arkham House collectors for two pieces of Derleth-related publisher’s ephemera: the first, a 1963 Candlelight brochure announcing his Three Literary Men and The Last Bookman.

Also in this brochure, a Sherlock Holmes statue sculpted by Luques Whitmore and four titles as forthcoming, though never published by Candlelight: John Jasper’s Devotion by Nathan Bengis (published elsewhere 1974–75); Fulminations of a Nocturnal Bookman by Russell Kirk (unpublished, apart from excerpts); Two Sonnet Sequences by Jacob C. Solovay (published by Luther Norris in 1969); and The Dog that Spoke French by Vincent Starrett.

Arkham House subscribers saw their first hint of Candlelight Press in 1964, items 62–64 on Don Herron’s “A Checklist of the Classic Years” ephemera; without citing Candlelight by name, Derleth’s blurb promotes “The Adventure of the Orient Express.” But in 1965 Books by August Derleth, in his typical Stock List format, with the Order Blank addressed to “Arkham House” — item 75 on Herron’s list — we find six Derleth books: one Mycroft & Moran, one Duell, Sloan & Pearce, one Prairie Press, and three, Candlelight!

As for Candlelight’s full slate of books, the press slowed in 1967–68 to only one book by Derleth and a cloth reissue of The Last Bookman, which suggests that funding separate advertising of its own had become prohibitive. For his part, in “Other Books from Arkham House / H&W Press Books” — a brochure mailed with early issues of The Arkham Collector — Derleth called out his Collected Poems: “A Candlelight Press Book. Coming September 1967.” A year later, in the subsequent “New and Forthcoming Books by August Derleth,” he described four new Candlelight releases, including A House Above Cuzco. In 1971, there were another six, including the new Return to Walden West…

In 1970 Candlelight was on the move again. Ruber managed even to publish a handful of items of personal interest, including Letter to an American by Kenneth Paul Shorey (not seen), and a new Candlelight brochure — the second ephemera piece of note; under the category “New” books, Derleth’s Return to Walden West, Love Letters to Caitlin, and The Three Straw Men. Also Marcia Master’s Intent on Earth. And The Office — A Facility Based on Change by Robert Prost. “Recent” books, Derleth’s A House Above Cuzco and The Wind Leans West. Also, the new The Last Bookman and Pictures from Hell, a poetry book by Luke M. Grande. “Forthcoming Books” included Master’s Grandparp, “Announced previously as When the Butterflies Talked,” Starrett’s Death Watch, and Derleth’s “revised and enlarged” Literary Papers — intriguing, for whose names he may have added, probably Jesse Stuart, H. P. Lovecraft, Maxwell Perkins and possibly Farnsworth Wright, even William T. Evjue.

Undoubtedly, it would be the final book in a Candlelight bibliography. Questions surround Love Letters to Caitlin. On November 26, 1988, in a letter to the August Derleth Society, a fan-based group, Ruber explained the sudden demise of his press:

The Caitlin book was never released. At the time of his death, all the pages had been printed, and three or four copies had been hard-bound by the Prairie Press to illustrate the finished product. Derleth’s lawyer suppressed the publication …. I recall being quite annoyed by his unilateral action, and angry words were exchanged. As a result, I closed down Candlelight Press, and a half-dozen important Derleth novels and short story collections that Derleth and I planned to bring out never saw the light of day….

To the best of my knowledge the list of titles below fully represents the six-year run of The Candlelight Press — all books plus two advertising brochures — an equal link in a chain that includes Mycroft & Moran, Stanton & Lee, and Hawk & Whippoorwill.

CANDLELIGHT PRESS

New York & Copenhagen

Candlelight Press (1963, catalog)

Three Literary Men (1963)

The Last Bookman (1963, paperbound)

Finch’s Final Fling (1963)

Strange Studies from Life (1963)

The Adventure of the Orient Express (1965)

Praed Street Papers (1965)

Wisconsin Country (1965)

Intent on Earth (1965)

Letter to an American (1965–68?)

Collected Poems (1967)

The Last Bookman (1968, clothbound)

Pictures from Hell (1969)

A House Above Cuzco (1969)

The Wind Leans West (1969)

Candlelight Press (1969, catalog)

Three Straw Men (1970)

Return to Walden West (1970)

Love Letters to Caitlin (1971)

John D. Haefele contributed this article.

© 2021. All rights reserved.

October 18th, 2021 at 4:46 pm

Just found out about this blog. Very interesting. I always liked Derleth.